Writings

Cryptography (and Security) for Coders

This page was written to supplement my Cryptography (and Security) for Coders talk at the Chicago Code Camp ’12. It is a significant improvement on an earlier talk, which had less of a programming focus (and actually contained a few errors.)

I should quickly but emphatically note that, even though we’ll be discussing several crypto algorithms, which you should definitely use, you should never implement these algorithms. If you do, you’re very likely to have a perfectly correct system that is susceptible to side-channel attacks (e.g. timing attacks, padding oracles, etc.) Instead, use open source libraries which have been publicly and thoroughly vetted.

Encryption

Encryption is actually a pretty simple concept. It simply means that we take an original “plain text” (i.e. that which you want to hide) and converting it into some gobbledygook (ciphertext) with the stipulation that you can reverse it, getting the original plain text.

Let’s consider an example. Think of the algorithm (ROT2) that takes every letter in the plain text and increments (lexicographically) each letter twice, wrapping around at ‘z’. This algorithm would turn the plain text ‘how are you doing?’ into the cipher text ‘jqy ctg aqw fqkpi?’, as ‘h’ becomes ‘j’, ‘o’ becomes ‘q’, etc. The decryption algorithm (i.e. ROT2’s inverse) should decrement each letter by two, turning ‘c’ into ‘a’, ‘d’ into ‘b’, and so forth, wrapping at ‘a’. We could accurately describe this as ROT-2 (rotate-negative-two).

Here would be a good point to note that no modern encryption relies on a secret algorithm. In fact, the more widely known your encryption algorithm, generally, the better of you are, as that implies the algorithm has been publicly vetted and reviewed. Instead of a secret algorithm, we rely on a secret parameter to the algorithm, known as a “key.” In our previous example, ROT (or rotate) would be our public algorithm, and “2” would have been the key. If we had used “7” instead, we’d have quite different output.

The key, then, becomes like a password. Whosoever has this key has the ability to encrypt/decrypt data. This causes a new concern, “key management,” as we need to limit who has access to these keys. We’ll talk a bit more about this below.

You might be thinking that encryption is all well and good, but why do I need to encrypt user data? One reason sticks out above others: at some point, your data will be released. This may be from some Russian super-star hacker, it may be a script-kiddie; it may be your competition, or it may be a former employee; ultimately, your data will be visible to someone you didn’t intend. At that point, you want the raw data to be as worthless as possible.

That’s not the only reason to encrypt, however. In many cases, hiding data from yourself is a good idea. Imagine that your application needs to keep track of users’ social security numbers to perform de-duplication. Aside from this one task, there is absolutely no reason to know the SSN, so it would be a good idea to hide the SSN from yourself by encrypting it (and only decrypting when de-duplicating.) I’ll take a brief detour here and emphasize that if certain data (e.g. users’ names, their location, etc.) is not relevant to your business, you should not be storing it. The less data you store, the less data is at risk when you are attacked.

You might also want to use encryption as a means of limiting certain users/services from accessing data. For example, your email sub-system probably needs access to your users’ email addresses and names, but it likely doesn’t need the users’ genders. If your email system was compromised, you don’t want the gender info to also be leaked. This is another layer on top of using different database users.

Finally, you might use encryption to verify authenticity of the encrypting party. We’ll talk more about that shortly.

Key Management

As I mentioned above, keys are a bit like passwords, and like passwords, the longer the key, the harder it is to guess. Unlike passwords, keys should be too long to memorize -- modern symmetric keys are between 128 and 512 bits, while modern asymmetric keys are between 1024 and 4096 bits. As we can’t memorize these keys, we’ll need to store them somewhere, and where the keys are stored turns out to be a particularly large problem.

At first blush, we might think that the database makes sense -- that is where data goes, afterall. Unfortunately, this would be a wrong solution. In this situation, an attacker who managed to steal your database would have both the encrypted data and the keys needed to decrypt it, resulting in almost no benefit from encryption.

We should instead aim to keep our keys as far away from the data as possible, and by this I mean that the key should only be available at the last possible moment (i.e. right when the data needs to be decrypted.) The ideal solution would be to have a database server which has all of the encrypted data but no keys; the keys would only be available on the client-side. Obviously, this solution won’t work for all architectures, but it is a worthwhile goal.

Note that I did not say we should use database-level encryption. Generally, these solutions imply that the data is stored in an encrypted format on the disk and that connections must provide the correct decryption key. While that’s certainly valuable if you are concerned about someone accessing your file system, it doesn’t help us when our database connection is compromised. If a subsystem is compromised, its connection to the database will surely also be compromised.

Instead of database-level encryption, we want to be a bit more “granular” with our keys. By this I mean, we should use different keys for different subsets of data. For example, you could have one key for the whole “user” table, or one key for each column in the user table, or one key per row, or some combination of these. In any case, the more granular your keys, the more control you have over who has access to the data -- you just need to limit access to the keys. Here, keys are kind of like firewalls. They certainly offer “defense of depth,” that is, compromising one key shouldn’t mean a catastrophic data leak.

In the case of a compromised key (e.g. through an accidental email, an employee leaving, etc.,) you should re-encrypt your data, that is: decrypt with the original key, generate a new key, and encrypt with the new key. In general, you should be periodically re-encrypting your data. This limits your exposure when data or keys are leaked. Remember also that the re-encryption process is completely automate-able, so this shouldn’t be a challenge.

One more quick note. Don’t share keys between development and production environments. Ideally, your developers shouldn’t have any access to the production keys. Only a limited number of individuals (e.g. CTO) should have access to production keys. This way, an angry (or naive) employee won’t be able to affect your customers.

Symmetric Encryption

Symmetric encryption is the form where the same key is used for both encryption and decryption. You will use this form of encryption when you have control over both encryption and decryption servers (and hence can install the proper keys on both.) Symmetric encryption is generally preferred over asymmetric because it is significantly faster; modern computer architectures actually have a special instruction to AES encryption/decrypt, so these operations are built into the hardware.

Let’s talk algorithms. Earlier I mentioned ROT2, which is clearly an awful algorithm, so what should you actually be using? If you go hunting, you’ll find algorithms like DES, 3DES (triple DES), AES, RC5, Blowfish, Twofish, and many others. Which is “best”?

First, let’s get rid of the “broken” algorithms. In particular, you should never be using DES, the data-encryption standard, which was adopted in 1979. This algorithm uses a very small key (56 bits), and a key can be guessed on modern processors on the order of a day or two. Triple-DES (3DES) is effectively running DES three times, with three different keys. The key size, then is 56*3 = 168 bits, but due flaws in the algorithm, its effective key size is only around 80 bits. This is still pretty strong (NIST suggests 3DES can be used until 2030,) but 3DES is very slow (DES is slow already, 3DES is approximately three times as slow.)

After DES was pronounced dead by NIST, a contest started to come up with a replacement. This competition produced five finalists: Rijndael (now, AES), Serpent, Twofish, RC6, and MARS. MARS proves to have a pretty serious flaw, and RC6 may not be a public-domain algorithm, but the other three will probably work well for your symmetric encryption needs. That said, Rijndael was selected (becoming “AES”) and has therefore been the most reviewed algorithm of the bunch. While new algorithms are certainly going to rise, for now, AES seems to be the clear winner.

A quick note about key sizes. AES offers key sizes of 128, 192, and 256 bits. It’s a good idea to chose 256 bits; while 128 should be fine, you should consider that the encrypted data may be decrypted at some later date (when 128 bit encryption is easy to solve.) 256 pushes that off far into the future.

Encryption Modes

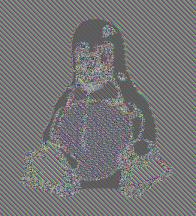

Now let’s discuss encryption modes. AES takes in exactly one block (128 bits) and outputs exactly one block. If you apply this blindly to your input, you are using what’s known as Electronic Codebook mode. Consider this picture of Tux

Electronic Codebook mode does nothing to hide repetition within the file. This means any block encoding a collection of white pixels will look identically to another block encoding a different collection of white pixels. This leads to information about the underlying content “bleeding through.”

In general, if you can test for equality after encrypting, you’re doing it wrong. So what other options do we have? No matter what, we’ll need to introduce some randomness known as an “Initialization Vector.” The idea is that you mix in a bit of randomness with your data and carry that randomness along in the encryption output. You can easily decrypt the data with the appropriate IV.

Cipher-block chaining (CBC) was one of the first solutions to this problem and continues to exist in many environment, even though it has many problems. For each block, it mixes in the encryption of the previous block with the encrypted output, making every block of the output depend on the blocks before it. Unfortunately, this algorithm doesn’t allow the individual blocks to be encrypted/decrypted in parallel, and any faults in the encoded text will be carried forward to all blocks following.

Here, Counter mode (CTR) is better. The initialization vector effectively serves as a counter which is incremented for each block and mixed in when encrypting. This means it is very easy to determine which value to mix in for a given block, allowing the encryption/decryption algorithms to be performed in parallel. This also means that fault data has very limited effects.

Both systems have a terrible fault, however. If an attacker has access to the encrypted data, he/she could alter the bits in such a way that the ciphertext with decrypt to a different value. Consider a secret message like “Transfer $0.20” which is encoded as cce2ed64a6e8c2dbb31ecef8b6122bf024487a80dbb3abfdf4e20307. If we know the original text and we know this was encoded in ECB or CTR mode, we might want to change this to “Transfer $9999” by modifying the bytes of the string: cce2ed64a6e8c2dbb31ecef8b6122bf024487a80dbbaabf6f4e5030e. When our system tries to decrypt this message, it will be the message the attacker intended, and we’ll lose a lot of money.

Instead, we want to use what’s known as “authenticated encryption,” which offers both privacy and tamper-resistance. If a message is altered, it will return an error when attempting to decode, which is precisely what we want. There are several authenticated encryption modes, including CCM, EAX, GCM, CWC, and OCB. Each has various benefits, but it seems that GCM is probably your best bet. While it is slower than OCB, OCB is patented such that its usage is heavily restricted.

So again, the moral of the story: Do not use ECB, nor CBC, nor CTR. Opt for GCM wherever possible.

Password Hashing

In this section, I’ll eventually try to push you towards an algorithm like scrypt, but let’s start at the beginning. Why shouldn’t we store passwords in plain text in the database? Here, we remind ourselves that our database will at some point be hacked, revealing user passwords (as plain text) to the attacker. Everyone uses a different username and password for every site, so this wouldn’t be a problem, right?

We just learned about how great encryption is, so why don’t we just use that? We could have 256-bit GCM AES encryption where only one person in the world knew the key and it was memorized, yet that wouldn’t be good enough for users’ passwords. As an application developer, you will never need to know the users’ passwords, so why keep them around? Encrypted passwords can be decrypted by someone, and that needs to be avoided.

Instead, we should use what’s known as a “hash,” that is, a function which converts an arbitrary amount of data into a fixed-size, gobbledygook fingerprint such that, given the same inputs, the hash will always return the same gobbledygook. This sounds good, but what algorithm should we use? md5 is popular, right? Let’s use that.

Unfortunately, md5-ing the password isn’t a good solution here. For one, consider what happens when two users have the same password. Would their md5 be different? No. Now you know more about your users’ passwords than you would like, and unfortunately, many users share the same passwords. The bigger problem, however, is in what are known as “rainbow tables” or “pre-image attacks.” You see, it’s quite easy to find the md5 (or any hashing algorithm) of the letter ‘a’, and the letter ‘b’, and the string ‘aa’ and ‘ab’, etc. until you have gigabytes and gigabytes of mappings from hashed output back to the original passwords. If you Google around, you’ll find that most passwords less than 10 or so characters can be found almost instantaneously from the md5 output.

We could pad the input, then, to avoid rainbow tables. What if we added a really long constant string? Now, as soon as an attacker finds this constant (which wouldn’t take long if he/she has access to one plain-text password,) he/she will be able to build a rainbow table specific to your site.

Instead, you’d want to use a random, long string known as a “salt.” Unfortunately, to check that a password is the same, you’ll now need to include the same salt generated when first hashing the password; your password now has a key. Where do you store that key? As before, the further away from the data, the better.

We can do much, much better though. md5 is a poor hashing algorithm. It has many collisions and extension attacks, which may not be directly relevant for password hashing, but these lend credence to preferring another algorithm. Sha1 is a good start, but has extension attacks. Sha256 and Sha512 are even better, and there’s yet another improvement we can make on this basic hash. Due to flaws in most hashing algorithms, it’s a good idea to “mix in” the salt using an HMAC algorithm.

We’re ignoring a really serious problem, however, which is much more significant that the differences between md5, sha512, and hmac. The bigger problem with simply hashing passwords is that hashes are largely built to be fast and this is precisely what you don’t want when someone is trying to guess a user’s password. You want the password check to be as slow as possible without annoying your users. Consider an algorithm that takes a quarter-millisecond to computer verses one which takes a quarter-second. The user won’t notice a difference, yet it would take an attacker 1000 more time to guess the password. This is known as “key stretching.”

To resolve this, the algorithm PBKDF2 was developed, which generates a random salt, takes a hash of the salt + password, takes a hash of that hash, hashes that hash, and so on hundreds or thousands of times (“rounds.”) In particular, this algorithm allows the number of rounds to be altered, so as CPUs improve, the number of iterations can likewise be increased. PBKDF2’s a good standard, but if you want to jump on a bandwagon, bcrypt performs basically the same operations, yet has gained a bit more support among web developers.

There is one more improvement that can be made to bring us to the cutting edge. While bcrypt and PBKDF2 are great because they require a lot of time (they are “compute-hard”,) they are very cheap to parallelize. In a few years, we will have 64-core processors, and the number of cores will steadily increase, which makes cracking a computer-hard hash easier. While we can’t stop these attacks, we can make it a bit harder (more expensive,) by requiring gobs and gobs of memory also be used. Here, “memory-hard” hashing functions like scrypt help us by requiring so much memory that they could not (in theory) be performed in parallel on the same machine.

You might be thinking to yourself, “Oh no! Our password hashes are awful, but how can I move existing passwords to a better system?” Luckily, for the most part, chaining hashing algorithms takes on the security of the best algorithm. Hence, if you are using unsalted sha512 right now, you can mass update your database by bcrypting all of those entries. When a user signs in, you would first sha512 his/her password, then bcrypt the result before testing the hash.

Authentication

Authentication is all about identity, specifically about verifying identity. You might think of a typical username and password login screen. Here the identity is defined by the username field and the password serves as proof of that identity. Presumably, only the person who owned the identity would be aware of the password, so by presenting the password, they are providing evidence of ownership.

Usernames and passwords aren’t the only form of authentication, however. Authentication falls into three basic categories of proof. There is that which you have (such as a passport, a debit card, or a key fob,) that which you know (like a password, your middle name, or your date of birth,) and there is that which is inherent to you. This last category is a bit complicated; it represents factors which are yours purely by the fact that you are yourself; they tend to be difficult to lose and difficult to give to others (e.g. your retina, fingerprint, and DNA.) This last category is particularly difficult to verify remotely, so we tend to focus on the first two.

If you’ve heard of two-factor or multi-factor authentication, it specifically refers to any authentication mechanism which requires evidence from two or more of the above categories. For example, Google provides two factor authentication where they send a message to your phone (that which you have) which you must enter in addition to your password (that which you know.) Multi-factor authentication is a very good idea and is used for the most sensitive data. For example, ATM transactions require your card (something you have) and your pin (something you know.) The more forms of evidence someone can provide, the more assured you can be that they are who they claim to be. It’s best not to get carried away, but surely you can imagine situations in which a password alone is not the best option.

Going back a bit, what alternative do we have to the traditional username/password schemes? Let’s consider what happens when a user logs in. The server generates a random session token which it then provides to your browser as a cookie; in all subsequent correspondences during this session, the browser will provide the session token back to the server. Effectively, this interaction has converted that which you know (your password) into that which you have (your token.) Note that it’s essential that the token be randomly generated and be relatively long to prevent any others from guessing the token during its lifetime. SSH keys fit a similar role, but they do not expire; to account for this, most SSH keys are very, very long.

Both of these mechanisms are still single-factor authentication. We can modify the SSH scenario so that use of the private SSH key requires a password to be manually entered. For a website, we could limit logins by IP address, which would add additional evidence of identity. Limiting access by IP might be seen as something owned or perhaps inherent to the user; in either event, it’s relatively transparent to the user. Perhaps a session cookie is enough verification when sent from an expected IP address, but a password is required when send from an unexpected IP.

In addition to using multi-factor authentication, it would be a good idea to check for anomalies during the user’s session, and perhaps request re-authentication. Anomalies might include a new ip address, user agent, etc. for the same session token. Multiple sessions from the same IP may be not be an anomaly, but hundreds might be a sign of an attacker, as would hundreds of session creation attempts. When authentication fails, you should use exponential timeout. This means, you should prevent another authentication attempt from that IP (or for that user) unless a quarter second passes. If the authentication fails again, require half a second, then a second, two seconds, four, eight, etc.

To close, I’ll make note of a few additional authentication related features you might consider. First, whenever a user changes authorization level, you should generate a new session id. This prevents users from accidentally giving privileges to another user’s session. Javascript can also be used to your advantage when you are concerned with authentication. You can use it to both locally log a user out after a defined period of inactivity and to locally log a user out when he/she closes the window/tab.

Injection

Injection is currently the number one security risk in the OWASP top ten. An injection attack occurs when an attacker adds (“injects”) new code into your application. It is most commonly associated with a subset called an SQL injection, so we will consider that subset first.

SQL injection is a relatively widely-known vulnerability for applications which do not properly sanitize the queries they send to their database. Consider the following PHP snipper,

“SELECT * FROM user where username = ‘” . $_POST[‘username’] . “’”The goal is to retrieve all information about the use whose username matches the POSTed input field, and if the attacker plays nice and only sends user names, that would be no problem. Consider if the attack sends the input “’ OR ‘1’ = ‘1”. The query now checks for a user whose username matches ‘’ OR any user where ‘1’ = ‘1’, i.e. all users. Consider the input “’; DELETE FROM user WHERE ‘’ = ‘”. Now, the database attempts to find all users with the username ‘’. When that query ends, the database proceeds to delete all users. Not quite what you expected?

The problem here is the use of string concatenation when generating the SQL queries. Because the user input is inserted directly into the query before becoming sanitized (read, escaped), there are no guarantees what query will be executed. One solution to this problem is to use placeholders. Now your query becomes

“SELECT * FROM user WHERE username = ?”and $_POST[‘username’] is provided as a parameter. It’s now the duty of your database abstraction layer to determine the best way to escape the input (whether it be a string, an integer, etc.)

Another option would be to rely on a query framework. Object-relational mappers and the like are usually built to allow a querying mechanism which will hide the error-prone SQL from you. With them, you’d see something like

users.filterEq(“username”, $_POST[‘username’])Now, you’ve probably all seen that example, but let’s consider the following:

“SELECT * FROM node WHERE nid = ” . urlSegment(2)Presumably, this fragment grabs the node whose id matches the third segment of the url (e.g. 25 in /node/25). Unfortunately, this is no better than the previous example, as the url is provided by the user. One could encode the same injection attacks via a well-encoded url as they could through a text-box. As a security-conscious developer, you should be weary of any input a user provides.

What type of input does a user provide? Obviously, the POST and GET parameters (typically coming from forms) are user input. This includes any hidden field that you have generated or any drop-down menus which you have populated; users can easily tamper with these hidden fields and submit selection which were not originally available, so do not assume that they are limited. As we just mentioned a moment ago, the entire url should be considered user input. This includes the domain name, as a user could easily modify their hosts file to redirect incorrectly. Any cookies that a user provides should also be suspect, even the session id. If you happen to use the user agent, referrer field, or anything else in the header, you should also recognize that these fields are provided by the users and could easily be forged.

SQL isn’t the only style of injection attack, however. Let’s next consider a script or dynamic injection. These attacks are most commonly found in a dynamic language, though there is the potential to create similar problems in statically typed languages. The crux of the problem is that code which has been provided by the user is executed dynamically. Many languages have the ability to interpret code dynamically, such as the PHP “eval” method:

eval(‘$myvar = ’ . $_GET[‘myvar’])Here, a mischievous user could provide any value for myvar, including “1; execu(‘rm -rf *’);” which has the potential to delete your webapp. Dynamic variable names, method names, and file inclusion all provide similar vulnerabilities. If you absolute need to use them, make sure to keep a white-list of acceptable strings.

Let’s also consider shell injections. This may occur if your application ever runs an external application with input provided by the user.

exec(“xmlstarlet ” . $_GET[‘filename’])Unfortunately, if the user provides the filename “; rm -rf *” he/she has once again deleted your app. The attacker could also pass the filename “`rm -rf *`” which would perform the same action. Now imagine if an attacker used the filename “somefile.xml; echo ‘replaced’ > /home/yourusername/.ssh/authorized_keys”. Now he/she could ssh into your box, a much more serious offense.

Note that injection can also occur on input display. Consider that you ask for usernames and a user enters <script>alert(“XSS!”);</script>. Unless you properly escape this when displaying to the screen, any user who sees that user’s username, will get a javascript alert message. This applies not just to HTML, but every place where user input might appear (e.g. a username is the URL, or an automated email.)

In closing, here are some rules of thumb. Never attempt to manually escape user input with regular expressions - you will miss something. Relying on the functions built into your libraries is a significant improvement, but again, you should try not to depend on them. Bugs are routinely found in these libraries. Instead, try your best to architect around the use of dynamically executed code wherever possible, and try to make use of white lists (rather than black lists.) Finally, follow a system of least privilege -- do not allow your web server to write files; do not allow the database to write to delete from the log table; etc.

Logging

Logging is an often-overlooked, yet critical aspect of security. Logs are a great source of information when debugging, performing security audits, and gathering metrics, but they also may reveal information about your application and/or users that you did not intent. There are three general factors to keep in mind when designing your logging systems.

First, let’s consider permissions of your logging system. For the most part, you want whatever is producing the logs to be write only. This prevents your log files from accidentally becoming public. In particular, it’s absolutely essential that your log files not be accessible from the net. Similarly, you’d like your log analysis software to be read only -- it should never need to alter the logs. This is a great use for public-key (or asymmetric) encryption, as you can use one key for encrypting and the second for decrypting the log files.

Other defense-of-depth measures include using a separate partition for the log files, and using a separate database or database user for logging. Again, these mechanisms add additional firewalls between an attacker and your log data (which may include confidential information.) When an attacker is successful at compromising your server, they will also likely attempt to clean their tracks from your logs, and these types of firewalls help prevent that. As an extension of this, it would be a good idea to periodically move log files to read-only media.

Second, you should take special care to not log certain, sensitive pieces of information. Image if you spent weeks implementing the perfect password hashing system, but the passwords were still kept in plain-text in your logs? If at all possible, try to blank out user passwords (and other confidential data) when logging. This isn’t just for your users, though, as you may accidentally log your own encryption keys or business-critical information. It’d be beneficial to destroy your logs as quickly as possible. Obviously, this will depend on your environment, but aim to have periodic log erasure or limited-size log files.

Finally, consider tamper-prevention logs. Your application can cryptographically sign all the logs that it produces, which would let you know immediately if the logs have been tampered with. As I write, there are efforts to enforce this on the Linux system log.

Asymmetric Encryption

We’ll explain asymmetric encryption with a little story. Once there was a very good-looking man, he was neither too fat nor too lean. Because he received too many love letters, he decided to hide himself away from his perspective suitors. Instead of living in a tower out of reach, he declared that he would “encrypt” his body by eating 1024 Big Macs. Once this was done no one could recognize his former self. He started courting various men and women, asking each to for the decryption algorithm which would get him back into shape. Many tried, but always he would end up too fat or too thin and hence his suitor would leave him and he would eat enough Big Macs to return to his encrypted weight out of shame. Eventually, one suitor proposed he perform 2 million and 19 sit ups. This proved to be the magic number, as he returned to his previous glory. They lived happily ever after as plain text.

This rather long-winded analogy does map to asymmetric encryption; there are a pair of distinct actions, one used for encryption (eating the Big Macs) and the other used for decryption (the sit ups.) In general, either key could be used for encryption just so long as the other is reserved for decryption. This is markedly different than symmetric encryption where a single key could perform both actions.

One common idiom of asymmetric encryption is “public key” cryptography. In these scenarios, one key is distributed publicly, e.g. through GPG key servers, on the user’s web site, or through some other authority. When an owner of a public key wants to prove authenticity, (s)he will encrypt (or sign) the message with his/her private key which can then be decrypted by anyone using the public key. As only the private key can encrypt something decrypt-able by the public key, it is clear that the message came from the owner. On the other hand, if someone wishes to send the own a confidential message, his/she need only encrypt the message with the public key. As only the private key can decrypt this message, the message’s confidentiality is guaranteed.

Asymmetric encryption is also commonly used for key exchange. Until now we’ve more or less assumed that if two services needed to communicate with each other, they must first have a shared, secret key. Asymmetric encryption solves this problem for us -- just generate a random key and encrypt it with the recipient’s public key. While there are other systems which generate shared keys (e.g. Diffie Hellman,) the asymmetric method is used most often in protocols such as SSL and SSH.

Let’s briefly touch on some divisions within asymmetric encryption algorithms. Presently, there are three popular algorithms, ElGamal, RSA, and various elliptic crypto schemes. ElGamal isn’t as popular in practice, but is used pretty widely in academia. It’s studied because it offers some interesting traits, like the ability to perform some operations on the underlying plain text without decrypting. ElGamal is also an option in PGP/GPG, which create offer secure email transfer options; DSA, the digital signature algorithm, is also a variant of ElGamal.

RSA is the most popular of the bunch and in many circles has become synonymous with public key cryptography. The founders, Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman, went on to start their own company which shares the name of the algorithm. This company has been very influential over the years, helping found VeriSign, and pushing DES to its limits with “DES Challenges,” which tested how long it would take to break a DES key. Returning to the algorithm, RSA is quite sensitive to the input it is given; sending a null message (or 1) would result in no encryption, for example. As such, it’s very critical that when using RSA, you use the latest revision of their padding standard, PKCS#1. That said, it’s an even better idea to avoid this all together and use tools (such as GPG) to manage these bits for you.

The final major form of asymmetric encryption is that of elliptic encryption algorithms. These are a current area of hot research but thus far they appear to be a better form of encryption. They appear to provide all of the security of RSA/ElGamal with much smaller key sizes (e.g. 128-bit elliptic key translates roughly to a 3072-bit RSA key,) a smaller memory footprint, and simpler operations. That said, adoption has been relatively slow, particularly due to some potential patent restrictions.

Let’s not discuss some of the practical differences between asymmetric and symmetric encryption. First, you’ll notice that asymmetric encryption is significantly slower, to the point that most asymmetric algorithms are used to establish a symmetric key which is then used for future operations. Similarly, when used for signing, asymmetric algorithms tend to only encrypt a hash of the document rather than its entirety (as could be the case with symmetric systems.)

While its not a requirement, most asymmetric algorithms rely on the difficulty of other “hard” problems (such as the discrete log problem, factoring large primes, etc. This means that they have generally been vetted well by the academic community, but also means that there could be some solution lurking within the math of which we are simply not aware. Many conspiracy theorists will claim that the US government has a secret, large prime factoring algorithm, and we have no way to disprove this.

All this said, I want to re-iterate that particularly with asymmetric encryption, there are lots and lots of ways to leave yourself open to attacks. Please rely on high-level toolkits (such as GPG) to handle key generation, message encryption, and the like. The authors of these tools have spent a lot more time thinking about attack vectors and vulnerabilities that you or I ever will.

SSL

To provide some motive for this section, consider what happens when you perform a Google search. You open a connection to Google’s servers, which send you an HTML form. You fill in your search term and then POST that to their servers, which then return your result. You are sending this information as well-formatted text and Google is responding with well-formatted text. There’s a segment (a few, really) that I left out in this description: you are not speaking directly with Google’s servers. Instead, there are many servers in between you and Google which are helpfully forwarding on your request. Unfortunately, as the messages are sent in the clear, they can also snoop on your information. Worse, any computer listening to these connections (e.g. all the users connected to an unsecured wireless access point) can also read your conversation.

This does have some benefits. In particular, it meant that ISPs could cache relevant content for their users. If you wanted to retrieve the New York Times home page, Comcast or ATT or whoever would recognize that this request has been made by other users and serve you the cached content. This is good for you, as you get your content quicker. It’s good for the NYT because they don’t have to re-render the page. It’s also good for your ISP since they won’t have to pay for the bandwidth.

Plain text communications can work for many situations but they certainly don’t work for confidential information. This is where SSL (the Secure Sockets Layer), which is almost identical to TLS (Transport Layer Security) used in HTTPS (Hyper Text Transfer Protocol Secure,) comes in to play. All SSL-enabled servers have generated a public-private key pair. When a client requests the connection be secure, the server responds with its public key. The client then verifies the key (we’ll discuss this later,) generates a random, symmetric key, and encrypts that key with the server’s public key. As only the server can decrypt this, we now have a shared, symmetric key. This effectively creates a secure tunnel which provided both integrity and replay prevention (a node along the way cannot copy some of the conversation, replay it later, and expect the same response.)

SSL is particularly important when it comes to preventing session hijacking, which used to be a very serious issue. Facebook, for example, required SSL when signing in, but after verifying your password, they would return a new session token which you would then share in the clear. This led to the development of a very cool little Firefox plugin called Firesheep, which would listen to your wireless network, waiting to see one of these Facebook tokens appear in the clear. It would then use that token to find the associated user’s profile image, and then provide you with a list of all logged in user images, asking you who you’d like to be today.

Firesheep certainly put the fear in Facebook, Google, Twitter, and their ilk, all of whom are not pushing an SSL everywhere strategy. I would strongly encourage you to do the same: restrict access to your web app to HTTPS. This won’t cost you much -- aside from the initial key exchange all operations occur via symmetric encryption, meaning they are lightening fast. You can even set up an HTTP redirect on port 80, just in case someone attempts to connect there.

One note if you manage the HTTPS route, be sure to restrict all of your page content to HTTPS. If you have any images, JS includes, etc. over HTTP, users will receive a “mixed-content” warning. While this is annoying it makes sense -- HTTP content over a secure connection effectively opens a trap door which can spill out revealing information from your connection.

Let’s now talk about SSL server configuration. You’ll start by generating a key pair via a program like openssl. You may then want to get your certificate signed by a certificate authority (more on this later,) but ultimately you’ll have a public and private key that you need to configure your server to know about. Once you’ve set your server to use the correct files, you should be good to go, but there’s a few more tweaks we can make.

First, I stated before that the client uses the server certificate to verify that the server is who is claims to be. You can perform a similar action on the server side, restricting access to only certain clients. To do this, you must generate a new key pair, install this in the client’s browser, and install the public key in the server’s keystore. Another quick note here, as the TLS/SSL protocol occurs at a lower level than HTTP, you will not be able to have a different SSL configuration per domain name; instead you can only have one configuration per IP-Port combination.

Second, I should make you aware that web servers generally try to negotiate with the client when establishing a secure connection. Unfortunately, these negotiations can be damning, as they allow the possibility that you’ll settle on an insecure crypto protocol. As such, I think it’s important to specify exactly which ciphers can be used when speaking with a client. The list I use for our servers is: SSL_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_MD5, SSL_RSA_WITH_RC4_128_SHA, TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA, TLS_DHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA, TLS_DHE_DSS_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA, SSL_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA, SSL_DHE_RSA_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA, SSL_DHE_DSS_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA, all of which are secure for now. This could mean that you deny certain clients access to your server, but this list encompasses all legitimate browsers developed in the past few decades.

Finally, I wanted to spend some time shedding light on certificate hierarchies. After generating a certificate, you will generally apply to one of the many certificate-signing authorities (e.g. Verisign, Thawt) to have them sign your certificate. These agencies will charge you through the nose and send you an email verification, followed by a signed form of your public key. Now, when a client asks your server to authenticate, your server will respond with the public key of the certificate-signing authority, your public key, and a signature of your public key with the CA’s private key. The client’s browser looks up the CA, determines if it is a known CA (i.e. in the set of CAs built into the browser or OS) and then verifies the signature. If everything works out, the client trusts that your server is who it claims to be because you have the backing of a CA.

This is a bit of a cabal. The CAs simply declared themselves trustworthy while SSL was being developed, and the browser makers agreed. Unfortunately, this means that on occasion, a CA will lose control of its private key, which happened to Comodo a year or so back. All of the major browsers had to push a revokation of Comodo’s keys to protect their users from malicious certificates. The hierarchy also means that you will most likely need to pay large sums of money for almost no reward. You could self-sign, but this will produce a warning message in most browsers. There are alternatives based on a crowd-sourced model, but none have gained enough traction to be viable at this point.

Searching Encrypted Data

This is a topic very dear to me because it comes up very often in practice. Once you’ve encrypted data, it looks like noise. You can’t easily sort it, filter it, or aggregate over it as you could with a plain-text database. There are some techniques to overcome these issues, but I should give a strong warning: by definition, each of these methods makes your data more insecure. The encryption methods above were developed explicitly to prevent information leakage, yet that’s exactly what we need when searching through encrypted data. As such, you will be circumventing your own defenses!

The first problem we’ll discuss is that of looking up an entry. Say you use email addresses as usernames (a practice which should be avoided.) The email address should obviously be encrypted, but you also need that information to look up a user when an authentication attempt is made. Kicking off a map-reduce job to decrypt all of the email addresses will be far too slow, so what options do you have? The encryption modes we’ve discussed thus far won’t help us because they add randomness (a random IV) to the data.

Why did we add that IV again? The random IV masked patterns in our data -- it prevented an outside observer from noticing when multiple users shared the same first name, for example. Here, we are assuming that email addresses are unique within our system, so this concern is lessened. Can we get rid of the randomness? Encryption schemes which always result in the same output given identical input are known as deterministic encryption schemes.

So, what are our options? A simple solution would be to use a deterministic hashing scheme a la md5, sha256, etc. Unfortunately, as we already discussed, rainbow tables already exist for these common algorithms which would negate our efforts. We should instead use an HMAC with a secret key. These efforts all require storing a separate, hashed form of the data.

We can instead modify our encryption scheme. Using ECB mode is still a mistake; while it is certainly a deterministic algorithm, we could easily see repeated cipher blocks. We will instead keep our authenticated encryption, but use a constant IV instead of one we randomly generate. This constant IV acts very similarly as the secret key in the HMAC algorithm above. There is yet another possibility, if you are willing to wade through some academic papers. A proposal for a “Synthetic IV” emerged a few years ago which offers deterministic, authenticated encryption without requiring a unique key. I know of no crypto libraries that implement this encryption mode at the moment.

Next, let’s consider finding a set of elements that have a shared trait -- filtering the data. Again, this may seem impossible at first, but let’s persist. Think of how a database would perform the same operation on plain-text data. In the most simple case, it would check every row for the requirement and build up a collection. If this operation were performed often (or if the operator explicitly told the database to,) the database would generate an index for this query, keeping a mapping of all rows which shared said trait.

We can do the same. Imagine an index for the shared trait which was stored, encrypted elsewhere in the database. To perform a filter then, you’d simply need to decrypt this index, and use its results to fetch the final set of rows. Now it is up to your application to keep this index up to date, but with it, we’ve managed to solve the filtering problem without giving too much away. Similarly, if you needed a filtered list, you could likewise create a sorted index.

Now, let’s consider the hardest case. For reporting purposes, you need full access to all of the decrypted information in a format that can be sorted, filtered, and full-text searched. You should rightfully be taken aback by how difficult this will be using the methods described above. I have yet to discover a method which will allow these operations in anywhere near as secure a fashion as even the lookup and indexing methods described above. Instead, the best option I’ve used has been an in-process, in-memory database, such as H2, of decrypted information.

Here, I’m going to throw up more warnings. Even though we will limit the database to be in-memory (hence it will die when the server dies) and in-process (and inaccessible to other processes) and perhaps even anonymize the data, we’re opening up a huge hole for attackers to target. We are tightening the perimeter, but we’ve effectively removed all security within. Do not take this lightly, and please, please, please be careful.

To close, I thought I would briefly note some of the current research in this area. Much work is being performed on homomorphic encryption, which are encryption methods that allow the plain text data to be manipulated after encryption. In particular, lattice-based encryption has proven that arbitrary mathematical operations could be performed on the underlying plain text. Unfortunately, these methods are terribly, terribly slow and are almost never used in practice.